Queen Victoria TheMET(5) flickr photo by rverc shared under a Creative Commons (BY) license

In some ways, fantasy writers have it easy. Whenever you need something a little more technologically advanced than your setting, you wave a magic wand. As a reader, this drives me insane. I am one of those detail-oriented, read all the directions twice, and count the screws before assembling the bookshelf people. I can't shut that off. Although I loved the Harry Potter books, the quill thing always threw me off because fountain pens were first advertised in the mid-1600s. For fellow Harry Potter fans, this means that fountain pens existed before the Statute of Secrecy.

In this case, I kept reading. Here's the thing. The more times an author tosses me out on my ear, the less likely I am to finish their book.

Here are three things either invented or perfected by Victorians that stand between me—your reader—and your story.

Even though I'm calling out historical romance here, fantasy authors are just as guilty. *waves*

Linoleum

!["George Harrison & Co (Bradford) :Linoleum, 2 yards wide. [Victorian scroll and classical pattern]. No. 122/2. Pattern shown half size. [1880s?]" flickr photo by National Library NZ on The Commons https://flickr.com/photos/nationallibrarynz_commons/20986565864 shared with no copyright restriction (Flickr Commons)](https://kchester.com/content/images/2019/03/20986565864_4b691a3d53_k.jpg)

Flickr photo by National Library NZ on The Commons shared with no copyright restriction (Flickr Commons)

Invented by Fredrick Walton in 1855, linoleum was further refined in 1863. By the late Victorian era, linoleum was an extremely popular floor-covering.

Today, we use linoleum as a catch-all term for flexible sheet flooring and tile. Most of which is vinyl, not linoleum. True linoleum does not contain plastic. They manufacture it with linseed oil, rosins, cork, and pigments. Sometimes, you'll see linoleum marketed as resilient flooring.

When a Victorian character moves into a newly built home, they'll smell the distinctive scent of new linoleum. Like most cork flooring, linoleum feels warm under their bare feet. It cushions their footsteps. When your main character stomps down the linoleum-floored hall in his cavalry boots, there isn't an echo.

Pencils

Wikimedia Commons Photo by the Metropolitan Museum of Art CC0

Although pencils predate the Victorian era, they were not mass produced until around 1870. Before Joseph Dixon perfected the manufacturing process, pencils were an expensive tool used by surveyors, artists, and some writers. By the end of the Victorian era, Americans used more than 240,000 pencils per day. Hexagon pencils were invented by Ebenezer Wood sometime around the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign. American pencils didn't get erasers until after 1858, which is when Hymen Lipman patented a pencil with an eraser attachment.

Why all these random facts about pencils? Because details matter.

Hexagonal pencils do not belong in your Regency romance. If a character needs to erase a word, they must put their pencil down and then pick up an eraser unless your story's setting is in post-Civil War America.

Now, all of this ignores the bigger problem. If your story's premise is

Bettina, a maid in 1830s London, and Duke Macintosh fall madly in love. Separated by duty, station, and his wife, they continue their romance by correspondence, growing their affections until his wife dies suddenly and they elope to India.

You have a significant problem: literacy rates. In 1830s England, almost 60% of women couldn't sign their name on their marriage certificate. Illiteracy sharply declined after 1850. Odds are Bettina can't read. Maybe she can send him sketches instead. Better yet, perhaps she should fall in love with the good-hearted butcher who reads the duke's letters to her.

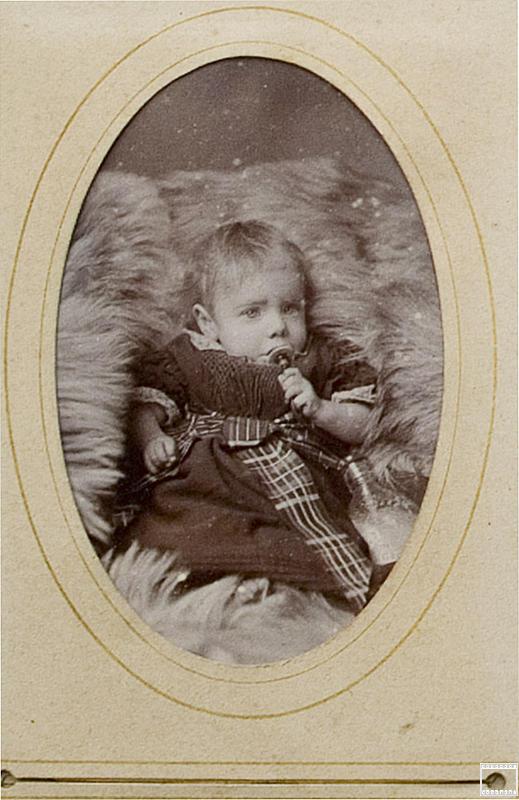

Baby Bottles

Flickr photo by whatsthatpicture shared into the public domain using (PDM)

When Elijah Pratt of New York patented the first rubber nipple in 1845, he kicked off a new age in infant care. For the first time, babies had a suckable alternative to the human breast. His invention paired well with C. M. Windship's glass baby bottle, patented in 1841. By 1870s, Liebig and Nestle both marketed commercial baby formula and baby bottles were all the rage.

So if your late Victorian story includes an orphaned infant, you may see all the shiny advertisements and think you've found the perfect solution. Not so fast.

Washing Pratt's nipples in hot water deformed them. You couldn't sterilize them, which turned them into a breeding ground for life-threatening bacteria. Borosilicate glass, a.k.a. Pyrex, was developed in the late 1800s and brought to market in 1915. Soda-lime glass is less resistant to thermal shock, making it more likely to break when boiled.

The tubed bottles, which look like they have a built-in straw, were particularly hard to clean. Not a problem for the Victorians! Mrs. Beeton's Housewife's Treasury of Domestic Information—the go-to book household management and child rearing book of the era—doesn't even mention boiling the bottles. She assures us that a little soap and a feather is all you need.

Do not fall into the miasma trap here. I'm using the Mrs. Beeton's 1883 edition. Queen Victoria's personal physician wrote about germ theory in the 1840s. John Snow (the doctor, not the broody Game of Thrones character) talked officials into taking the pump off the Broad Street well in 1854. Louis Pasteur conducted his research in the 1860s. People knew that microscopic organisms caused diseases. Unfortunately, those people didn't edit Mrs. Beeton's guide.

Picture this.

The year is 1890. Your MC's sister dies in childbirth. Being the virtuous woman she is, she moves in with her brother-in-law to care for him and her sister's three children during his time of grief. After consulting with the doctor and reading Mrs. Beeton's—thank goodness the literacy rate's improved—they decide to forego a wet nurse and use a more modern approach.

Love bloomed in John's heart as he watched Elizabeth waltz around the kitchen with a giggling babe on her hip.

We all like happy babies. I get it. But in the real world, this is not a happy baby.

If you're using 1800s or early 1900s commercial formula, does the baby have scurvy or rickets? Probably. Maybe your character listened to the most cutting edge medical advice and opted for Thomas Morgan Rotch's percentage method, which uses cow's milk, water, cream, and either sugar or honey.

That sounds better, right? The US mandated milk pasteurization in 1947. I don't care what you read on Facebook or Instagram. Raw milk kills. Our dear Elizabeth just gave a newborn a formula that it can't digest and that possibly includes E. coli.

Of course, this assumes the baby bottles and nipples aren't breeding grounds for harmful (read lethal) pathogens. There's a reason folks nicknamed the banjo-style (tubed) bottles "murder bottles."

Suddenly, the sweet Victorian romance novel overflowing with the healing power of love turns into an angst-ridden series of funerals.

Conclusion

Details matter.

Whether you're writing a historical romance or epic fantasy, imposing modern expectations like milk pasteurization on an earlier period creates unintended problems. As a reader, I'll forgive footsteps echoing off cork floors. While period-incorrect pencils and too literate maids may make me cringe, I'll keep reading if the story's good enough. A thriving, happy baby when there's no logical explanation (i.e., a wet nurse)...no. That's the point when I stop reading.

When do you?